http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/a-different-kind-of-a-victory-in-gujarat/99/ A different kind of a victory — in Gujarat Ujjwala Nayudu Shahwan remembers the day nearly 11 years ago that the Gujarat Police came to arrest his father Adam Sulaiman Mansuri alias Adam Ajmeri. He especially remembers how his mother pleaded with them, telling them her husband was an innocent mechanic and not a […]

Blog

-

May 19: Sri Lanka turns killing fields into tourist attraction

1. http://www.thestar.com/news/world/2014/05/18/sri_lanka_prevents_tamil_memorials_on_5th_anniversary_of_war_victory.html Sri Lanka prevents Tamil memorials on 5th anniversary of war victory Sri Lanka’s government marked the fifth anniversary of its civil war victory over ethnic Tamil separatists on Sunday by displaying the country’s military strength, while preventing Tamil civilians from publicly remembering their dead. The government’s approach highlights the deep ethnic polarization that […]

-

PFLP condemns Israeli killings at Nakba day commemoration

Fight Back News Service is circulating the following statement from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Occupation crimes on Nakba Day at Ofer will spark increased resistance

The occupation’s crimes at Ofer on Nakba day open the door to the escalation of yet more crimes against the Palestinian people, said Comrade Khalida Jarrar, a leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. She expressed the condolences of the PFLP for the martyrs, Mohammad Odeh Abu Zaher and Nadeem Nawara, who were killed by occupation forces during a demonstration marching towards Ofer commemorating the Nakba and in support of the administrative detainees engaged in an open hunger strike.

She wished a speedy recovery for the wounded injured in the confrontation. “It is clear that the terror of the occupation is increasing and expanding against the Palestinian people. Today a demonstration at Ofer was attacked, directly targeting Palestinian boys and shooting them with live fire at close range in cold blood, assassinating them, killing these two young men and injuring more,” said Jarrar. She called for the broadest participation in the martyrs’ funeral on Friday to make it clear that the young men who fall as martyrs are not alone. “The relationship between the occupation and the Palestinian people is that the occupation is a killer tyranny, and the Palestinian people defend themselves and resist this terror,” she said.

She noted that ongoing escalation by Zionist forces is expected, but that the Palestinian people will not be silent in the face of these crimes, confirmed by the confrontations throughout the West Bank and Jerusalem, especially in Ramallah, al-Khalil and entrances to Jerusalem city. Jarrar noted that this crime reinforces the Front’s conviction of the need to build a unified national resistance front of all factions to organize the strategy of the resistance in all of its forms.

“Popular resistance is a comprehensive concept which includes resistance in all forms to the occupation. It therefore should not exclude any form of resistance, as we are facing a settler colonial military occupation. As an occupied people we struggle in multiple fronts, at the head, armed resistance, civil disobedience and protests such as those against the wall. The struggle waged by the prisoners of freedom inside the occupation prisons is a form of resistance, as is anti-normalization with the occupation, and the political and economic boycott, as well as diplomatic and legal resistance, such as going to the International Criminal Court to put the occupation on trial for its crimes against the Palestinian people,” Jarrar said.

On the anniversary of the Nakba, she emphasized that the right of the Palestinian refugees to return to their land from which they were expelled is the inalienable right of the Palestinian people and is not subject to limitation. In fact, she noted that this is at the core of the conflict between the Zionist entity and our Palestinian people, stressing the need to uphold this right and reject any initiative that could affect this right.

Jarrar noted that the occupation and the Zionist movement have a clear strategy to make Palestine “the Jewish state,” which is no new strategy yet is repeatedly posed at the negotiating table with the blessing of the United States. “We reaffirm that the right of return is the essence of the struggle and that any demand for recognition of the Jewishness of the state or a national home for the Jewish people means the abolition of the historical fact that Palestinians were removed from their land. This is an attempt to liquidate the right of return. We must remain in open struggle with this occupation until it is swept entirely from our land,” she said.

-

Philippines: Condemn AFP’s war of suppression and widespread abuses in Mindanao! Wage widespread guerrilla warfare in Mindanao and across the country to defend the people!

The AFP is conducting aerial bombings, endangering civilian communities and causing grave trauma, especially among children. Communities are subjected to hamletting, and food and economic blockades. AFP troops are promoting gambling, drug use, and other anti-social activities; rape and sexual violations against women are on the rise.

MEDIA RELEASE

By Communist Party of the -

India: Murmuri ambush is the retaliation against the fake encounters, atrocities and white terror unleashed by the notorious C-60 forces!

Communist Party of India (Maoist)

Dandakaranya Special Zonal Committee

Press Statement12 May 2014

Dandakaranya Special Zonal Committee of CPI(Maoist) congratulates and hails the brave red fighters of the PLGA who carried out a daring attack on the notorious C-60 commando forces and wiped out seven of them, while grievously injuring two others on 11 May 2014 on Muranda- Murmuri road in

-

Nagesh Rao on How will Modi rule? Who is Modi and how will he lead?

See Also:

http://democracyandclasstruggle.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/india-cpi-maoist-spokesperson-comrade.html

http://democracyandclasstruggle.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/make-new-democratic-revolution.html

-

Minneapolis protests says: “Stop the wars – ground the drones”

Minneapolis, MN – A highly visible anti-war protest was held in Minneapolis May 17, with over 120 people joining the demonstration.

The protest was called to be part of a national round of local anti-war and anti-drone protests during the months of April and May. The Minnesota Peace Action Coalition (MPAC) initiated planning for the event.

The May 17 protest was organized under the call of ‘Stop the wars – Ground the drones’, with the additional slogans of: Zero troops in Afghanistan; ground all military and surveillance drones; end drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia; for a full employment peace economy, not more war; no new wars – hot or cold; and U.S. hands off Syria, Ukraine, Korea, Venezuela, Palestine and everywhere.

In the final days before the protest, as the crisis in Ukraine reached a new and dangerous level, the International Action Center, United National Antiwar Coalition and other organizations issued a call for local protests May 9 – 26 against U.S. intervention in Ukraine.

MPAC, which in the initial call for the protest included the anti-intervention demand on Ukraine, endorsed the national call for anti-war actions on Ukraine and listed the May 17 event as one of the actions being held around the country to speak out against the danger of yet another war.

Signs and speakers at the protest spoke to the demand against intervention in Ukraine and against a new cold war with Russia.

The Minneapolis protest gathered at the very busy corner of Hiawatha Avenue and Lake Street. After 45 minutes of holding signs and banners, there was a march to Walker Community Church for an indoor rally.

A statement issued by organizers said in part, “Since 2004, over 2500 people have been killed by U.S. drone attacks in Pakistan. In Afghanistan, drone attacks are increasing and the U.S. government plans to keep thousands of troops and drones in Afghanistan for years to come. U.S. drone strikes are commonplace in Yemen and elsewhere.”

The statement goes on to say, “The endless series of U.S. wars and interventions continues, including increasing military aid, expanding U.S. bases around the world and internal meddling in other countries through economic pressures overseen by agencies such as International Monetary Fund and World Bank.”

At the rally a member of MPAC also warned that the U.S. was preparing military intervention in Nigeria in the name of saving kidnapped schoolgirls.

“The U.S. military does not intervene to help people, the U.S. military intervenes in the interests of corporations and profits, not people,” said the MPAC member.

The planning for the May 17 protest was initiated by MPAC and endorsed by a broad range of organizations, including, AFSCME Local 3800, Alliant Action, Anti-War Committee, Coalition for Palestinian Rights, Freedom Road Socialist Organization, Mayday Books, Military Families Speak Out (MN chapter), Minnesota Immigrant Rights Action Committee, Peace and Justice Committee of Sacred Heart Church (St. Paul), Peacemakers of Carondelet Village, PeaceMakers of Macalester Plymouth United Church, St. Joan of Arc Church, Socialist Action, Students for a Democratic Society (UMN), Twin Cities Peace Campaign, Veterans for Peace, Welfare Rights Committee, Women Against Military Madness, Workers International League and others.

-

Is Past a Foreign Country?: Thinking About Adam Ajmeris in Saffron Times

– Subhash Gatade“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” – L.P. Hartley, The Go-BetweenSixteen year old Shahwan, from Ahmedabad, who is still waiting for his Class X results, was extremely happy that day, when India’s electorate gave its verdict. He hugged his Ammi and went out in his Mohalla along-with his brother Almas, yelling ‘we have won’, ‘we have won’. And not only Shahwan and his family members but one could witness similar joy in the houses of Mohammad Salim Hanif Sheikh, Abdul Qayyum Mansuri alias Mufti Baba and several others.Interestingly Shahwan’s tremendous joy with tears flowing down the eyes of his Ammi Naseem (40) had nothing to do with the fact that Mr Narendra Damodardas Modi, had delivered a ‘historic victory’ to the BJP.

Shahwan and his mother. File photo: Indian Express It was a strange coincidence that the day India’s electorate decided to give a mandate to the Modi led BJP to rule the country for coming five years also happened to be the day when Supreme Court of India in a historic judgment overturned a controversial decision take by him as home minister. It was related to the prosecution of those arrested for Akshardham attack under now lapsed Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA).Perhaps not very many people would remember today how Akshardham Mandir in Ahmedabad was attacked by two terrorists killing 37 people and injuring several others way back in September 2002. It was reported that both the terrorists were killed by commandos on the spot itself. Shahwan’s father Adam Sulaiman Mansuri alias Adam Ajmeri, a poor mechanic along-with four others were arrested from Shahpur and Dariapur areas of Ahmedabad in August 2003 by the anti-terrorism squad of the Ahmedabad police for their alleged role in the attack. The sixth accused was nabbed from Uttar Pradesh a few days later. The lower courts sentenced Adam and another person to death for his ‘heinous role in the conspiracy’ which was later confirmed by the Gujarat high court. Remaining four accused were sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for life.Pulling up Gujarat police for framing “innocent” people in the particular case a bench comprising of Justices A K Patnaik and V Gopala Gowda held that the prosecution failed to establish their guilt beyond reasonable doubt and they deserved exoneration from all the charges. The bench nixed their confessional statements being invalid in law and also said that the prosecution could not establish they participated in any conspiracy. After perusing evidence and lower court judgments, the SC bench underlined how the story of prosecution crumbles at every juncture. According to Indian Express ( 17 th May 2014) the bench blamed the home minister for:“clear non-application of mind ..in granting sanction,” since it was based neither on an informed decision nor on an independent analysis of facts..The court said the sanction was hence “void” and not a legal and valid sanction under POTA.

Shahwan remembers his visits to jail on Eid and his father’s breaking down on such visits telling him that he had nothing to give him for the festival. For Naseem, it was rather a torturous journey as her own relatives literally boycotted her for being ‘wife of a terrorist’ and was not even invited on any occasion and had to bring up her two kids by embroidery work and stitching ofburqa. The only saving grace was that her neighbours who had seen Adam grow before their own eyes helping his father in his tiny workshop and always ready to go extra mile in helping others never believed the police’s theory and continued to offer her moral support.People who have tried to look beyond the glitter and glitz would recount similar stories of pain and suffering at the hands of a callous administration and a biased civil society. One of the most discussed and rather most tragic case was that of a social worker Maulana Umarji from Godhra who went out of his way to maintain communal harmony in the area and also organised relief and rehabilitation for the needy. He was made to rot in jail for years together under the same draconian law POTA on the basis of a confessional statement of another accused taken under duress. Maulana was similarly acquitted by the courts. Tortured and humiliated by the police in jail, he died few months later.It is matter of days when Adam Ajmeri like other accused in the terror attack case would return home. For one who had lost all hope to meet his family again it would be like rebirth and he would definitely like to forget what travails he went through, and perhaps would like to make a new beginning in his life. It is a different matter that question will keep lingering about the impunity with which the state could frame any innocent and stigmatise one’s family for all their lives and how the state could be turned into a large torture chamber for the marginalised and the vulnerable.This strange coincidence about electoral outcome and Supreme Court’s damning remarks which had a bearing on the quality of governance reminds one of another not so glorious chapter in the state’s recent history. It is well reported that it happens to be the only state of the Indian Union where you find so many senior police officers and their juniors still languishing in jail for their alleged role in many of the encounter killings in the state.May it be the case of Ishrat Jahan, the student from Bombay or Sameer Khan Pathan or for that matter Mr Soharabuddin, or Sadiq Jamal all these encounters took place at night wherein none from the police force received any injuries, despite the ‘terrorists’ being armed with ‘latest automatic weapons’ (as was announced later) and the rationale provided for these killings was that they had come to kill Mr Modi and his other colleagues from the Hindutva brigade.Merely a week before the election results were out, Gujarat government had to face another humiliating moment in the Supreme Court itself about its plea seeking uniform guidelines for dealing with cases of encounter killings. The highest Court dismissed the pleas saying that there cannot be such an advisory in a federal structure. A bench comprising of Chief Justice RM Lodha and justices MB Lokur and Kurian Joseph said that:“Guidelines or advisory of such nature are not enforceable,” (read media report here)

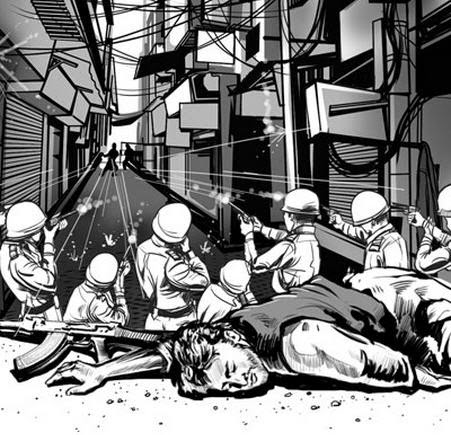

Creative depiction of fake encounter.

Courtesy: DNAIt may be noted here that the Gujarat government in 2012 had filed this PIL (Public Interest Litigation) for independent probe into all cases of alleged killings by police in past 10 years in the country and had sought direction to deal with all cases of fake encounters in a uniform manner. It had been Gujarat government’s contention that some vested interest groups are selectively targeting its police force over the encounter killings.The petition had sought a direction to all state governments and Union Territories to evolve and formulate a uniform nation-wide policy providing for an independent agency like “monitoring authority / special task force” created by the Gujarat government to probe into all cases of alleged fake encounters. An important aspect of this debate was that none of the BJP ruled states’ supported Gujarat government over this move and it found itself isolated.May it be the issue of ‘encounter killings’ in the state or for that matter the troubling developments in the year 2002 variously described as Gujarat carnage or Gujarat riots where according to his own party seniors ‘Rajdharma’ was not observed, it is clear that Mr. Modi begins his innings as PM of the country with a past which would keep haunting him.History bears witness to the fact that past just cannot be wished away claiming that it is a construct of the adversaries. All those people who tried to brush aside their past under carpet had to pay heavy price for their ‘amnesia’.Would Mr. Modi be able to make a radical rupture with the period gone by and turn a new page as far as not only good but just governance is concerned. That would be a moot question.Chances look really dim but as of now we have no other option than to wait and watch.**********Subhash Gatade is a New Socialist Initiative (NSI) activist. He is also the author of ‘Godse’s Children: Hindutva Terror in India’ ; ‘The Saffron Condition: The Politics of Repression and Exclusion in Neoliberal India’ and ‘The Ambedkar Question in 20th Century’ (in Hindi). -

Narendra Modi and the Barbarism of Neoliberal Dictatorship

Pothik Ghosh

“What are we waiting for, assembled in the forum?

The barbarians are due here today.Why isn’t anything going on in the senate?

Why are the senators sitting there without legislating?Because the barbarians are coming today.

What’s the point of senators making laws now?

Once the barbarians are here, they’ll do the legislating.Why did our emperor get up so early,

and why is he sitting enthroned at the city’s main gate,

in state, wearing the crown?Because the barbarians are coming today

and the emperor’s waiting to receive their leader.

He’s even got a scroll to give him,

loaded with titles, with imposing names.Why have our two consuls and praetors come out today

wearing their embroidered, their scarlet togas?

Why have they put on bracelets with so many amethysts,

rings sparkling with magnificent emeralds?

Why are they carrying elegant canes

beautiful worked in silver and gold?Because the barbarians are coming today

and things like that dazzle the barbarians.Why don’t our distinguished orators turn up as usual

to make their speeches, say what they have to say?Because the barbarians are coming today

and they’re bored by rhetoric and public speaking.Why this sudden bewilderment, this confusion?

(How serious people’s faces have become.)

Why are the streets and squares emptying so rapidly,

everyone going home lost in thought?Because night has fallen and barbarians haven’t come.

And some of our men just in from the border say

there are no barbarians any longer.Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

Those people were a kind of solution.– C.P. Cavafy, ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’

I

The barbarians have finally chosen their king. And this they have accomplished not despite the relentless squabbling they have been indulging in among themselves for the past couple of decades, but precisely because of it. Narendra Modi’s ascendancy as the fifteenth prime minister of India, let there be no doubt on this score, is not the emergence of some fascist political regime. It is something far more insidious, intractable and perhaps even unique in the political history of global capitalism. Modi’s electorally-driven rise as the leader of the executive branch of the government of India is the coming of age of neoliberal capitalism in this country. His ascension to the prime ministerial throne seals the neoliberal social process — which began unfolding in all its competitively anarchic and thus barbaric glory since the early 1990s – into a political dictatorship of neoliberal capital. Modi today stands for the institutionalisation of generalised barbarism.

And if there is anything more disturbing than this unprecedented victory for the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) then it is the unwillingness among its opponents in the various left, liberal and left-liberal camps to recognise this fact. Almost all of them continue to designate Modi’s electoral success — in the pragmatics of their practice, if not always in the overt claims of their theory – as a victory of fascism and a defeat for (liberal) democracy. Such reluctance on their part to recognise Modi’s rise for what it really is stems from their continued refusal to acknowledge the insolvency of the theoretical and conceptual presuppositions – conscious or not – that have been the orientating strategic core of their diverse political practices.

Such theoretical presuppositions have always tended to veer around to the strategic view that the constitutional tenets of the liberal-democratic Indian polity can be made into an effective bulwark against what they have always seen as the BJP’s fascist machinations. For instance, the insistence of many progressives across the board that the current model of development ought to become more inclusive by being based on the constitutionally-ordained principles of ‘secularism’ and ‘socialism’ reflects that. That, they believe, will save such development by cleansing it of the external impurities of communal and casteist violence and prejudice, thus enabling it to become the ecumenical dispenser of modernity and progress it is essentially supposed to be.

What such ways of seeing miss is that communal and casteist prejudice and violence are not mere externalities to the political economy of development. Rather, such political economy, in its current historical level and state of late advancement, can reproduce itself solely through multiple forms of social oppression. There can really be no question of inclusive development because capital, of which development is currently a euphemism, is not at all exclusionary. The problem with capital precisely is that it constitutes and reproduces itself by including all and sundry; but differentially. More accurately, capital is a structure of productive inclusion through hierarchical exclusion. That is to say, it can include only by excluding. In such circumstances, there can be no inclusion beyond such inclusion, or equality beyond such equality, unless that structure of capital itself is decimated. Inclusion beyond inclusion, or equality beyond equality, is, as Marx would say, not the equality of classes but their abolition.

It would, therefore, do our struggles against the Modi brand of politics a world of good, if we begin to recognise and register – not merely in the tenor of our rhetoric but in the programmatic orientation of our political practices as well – that the constitutionally-enshrined principles of ‘socialism’ and liberal-democratic secularism were ideological and formal expressions of capital in a certain moment of its historical development. This moment was the conjuncture of embedded liberalism when fascism and other illiberal politico-ideological forms that operationalised accumulation by extra-economic means were a constitutive fracture in liberal-democracy. The latter being the form of economic accumulation that operationalised itself purportedly through free competition, efficient markets, functional civil society and democratic polity.

But thanks to its relentless forward march, capital today is in a historical moment – has been there since, at least, the 1990s in India – when primitive accumulation (and the illiberal politico-ideological forms that operationalise it) is no longer the constitutive fracture in liberal-democracy that it had been earlier. Instead, the liberal-democratic form in the immediacy of its operation is substantively illiberal (fascistic, authoritarian and so on). As a result, liberal-democracy is not only not a temporarily effective barrier any longer against what is being perceived by both the leftists and the left-liberals as fascism but is, in real terms, the immediate formal actuality of various kinds of illiberal (including fascistic) substance.

In such a situation, it would be unforgivable to battle the ascendant rightwing politics of the sangh parivar from the vantage-point of liberal-democracy and constitutionalism. Unfortunately, that is exactly what all those who designate Modi’s rise as the emergence of fascism are guilty of; one way or another. Their ‘anti-sangh parivar’ politics continues to be integral to the reproduction of neoliberalism at a socio-economically substantive level, which is the vital condition of possibility for the legitimised emergence of the political form that will be the BJP-led NDA government. And this, may we also add, makes the practitioners and purveyors of such anti-Modi politics – whether radical, leftist or liberal — complicit in the strengthening of precisely the phenomenon they ostensibly seek to resist, combat and fell.

II

All those who are really serious about finishing Modi off in order to comprehensively destroy the political project his electoral victory both embodies and enshrines, need to understand that neoliberal dictatorship is the institutionalisation of the barbarism of neoliberalism. That basically amounts to liberal-democracy as oppression and the discourse of rights as negative determination being consensually accepted and legitimated as a settled juridico-legal regime, with the state as its institutional embodiment. In such an instance of the dictatorship of neoliberal capital, the institutionally crystallised form of the state becomes a mutually constitutive enabler and reinforcement of barbarism as a juridical-legal regime or state-formation. A neoliberal dictatorship is, therefore, the structural-functionality of a neoliberalised social formation congealing into a consensually accepted regime. The institutionality of the capitalist state is an adjudicatory/regulatory effect of social power as differential inclusion. In the case of neoliberal dictatorship, it becomes an institutionalised enshrining of the consensus of the neoliberal social formation that logically precedes it. Hence, it is a superordinate entity vis-à-vis the neoliberal society and is there solely to play a coercive role on the side of the more powerful in any given social relation of domination/oppression.

What we have, therefore, is a distinction of degree between neoliberalism as a phenomenon of generalised socio-economic barbarism, and neoliberal dictatorship as the legitimation of this generalised phenomenon of socio-economic barbarism into a settled juridical-legal fact. It is this difference of degree that might well turn out to be what sets the current Union government marginally but crucially apart from its predecessors of the past two decades.

The BJP’s decision to name Modi as its prime ministerial candidate, right at the very beginning of the electoral campaign, was a considered decision. This decision stemmed from its near-perfect reading of the social situation in the country as one that was eminently conducive, an ideal condition of possibility if one will, for the triumphant emergence of a figure such as Modi, and the utterly retrograde politics he personifies.

This condition of possibility was without doubt the tendency of social polarisation that more than lurked in much of north Indian society. But to merely describe it as that will yield not only a partial but also an erroneous picture of the social reality that has made this decisive victory of the BJP-led NDA possible. It will also mean that the concrete possibilities for building an effective resistance against this political institutionalisation of the Indian variant of neoliberalism remain unidentified, and beyond our grasp.

From such a standpoint, what is more important about this tendency of social polarisation is that it is has enabled a new nationalist reinforcement of the Indian identity through its redefinition and internal reconfiguration. Had that not been so, this tendency would not have been that effective, electorally speaking, for the BJP.

To understand this process of (re)production or renewal of the idea and reality of the new modern liberal Indian national identity, one will have to be attentive to the class/identity dialectic in the dynamic constitutive of the post-Independence Indian polity, particularly since the late 1980s and the early 1990s. That is, one will have to be attentive to the class/identity dialectic in terms of the intersection of the identitarianised politics of social justice, and economic liberalisation.

The politics of social justice, beginning in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, based itself on the competitive assertion of socio-economically and culturally subordinate identities against the dominant modern liberal identity by seeking to expose the latter for what it really was and still is to a large extent. The challenge that such politics articulated was based on the entirely valid claim that the modern liberal identity is a marker of a level of material development and ideological hegemony that some identity groups had achieved in the modern social formation of post-Independence India by leveraging their traditionally dominant positions in the pre-national social formation. Such achievement had, not surprisingly, also meant that certain subordinate socio-economically and socio-culturally identified groups had been denied this achievement of liberal modernity both in terms of material wealth and ideological hegemony.

The upward mobility of certain sections among the subordinate socio-economic and socio-cultural groups that resulted on account of this ambience of social justice politics, together with the explosion of new social, economic and cultural wealth, lifestyles and ways of social being that economic liberalisation unleashed for the bearers of modern liberal identity, have impacted that identity in two significant ways. They have led to a quantitative burgeoning of the demographic that ideologically subscribes and belongs to this identity, and have qualitatively redefined and internally reconfigured it both in material and ideological terms.

The quantitative burgeoning of the demographic of this identity has served to significantly reinforce the nationalist ideology of Indianness as the reinforcement and regimentation of an ever-increasing diversity of forms of embourgeoisement. Concomitantly, the neoliberal phase of ‘nation building’ — which has been shaped and determined by material and ideological/cultural demands of the socio-economic processes unleashed by economic liberalisation since the 1990s — has tended to create and deepen a new polarisation. There is, arguably, a growing schism between the modern-liberal Indian identity and those social groups, whose integration into that identity has been impeded by the dynamic of competition among traditionally unequal subject-positions. As a result, the latter continue to be materially less developed, leading them to ideologically and culturally self-characterise themselves in traditional identitarian terms.

This process of burgeoning of the demographic that subscribes to the ideology of the modern-national Indian identity, thanks to the upward mobility effected by social justice politics, is evident in the phenomenon of the huge and still growing middle classes and urban petty bourgeoisie. For, this social justice-fuelled upward mobility has primarily been about conversion of rural assets and rural socio-cultural capacities into urban economic assets and urban socio-cultural capacities by the upwardly mobile sections from among the various socio-economically subordinate and socio-culturally oppressed groups.

Now this has not wiped out social justice politics but it has most certainly served to decisively shift the stress from it to a new developmentalist discourse and practice of politics. It is this discourse of developmentalism that perpetuates, and articulates, the increasing diversity of socio-cultural forms as their underlying structural coherence or unity. Something that unites those diverse forms into a mutually competitive aspiration for and hierarchy of development. (Anti-corruption politics is an integral component of precisely such a discursive lay of the land.)

The upward mobility, constitutive of the modality of social justice politics, has deepened and accelerated class polarisation within socio-economically backward and socio-culturally marginalised identities that had, till the beginning of the 1990s, been relatively more cohesive and homogeneous.

Not surprisingly, such upwardly mobile segments of those identity-groups have increasingly been coming around to the necessity of tactically making common cause with their caste Hindu competitors (the traditional bearers of the modern, liberal-national identity) against the subalternised segments within their own identity-groups. This is probably one of the axes of social consolidation against those sections and segments, which by their very position and situation outside the idea and materiality of modern liberal Indianness pose a challenge to it. A challenge that continues to gather its political ballast and ideological force, thanks particularly to the paradigm of social justice politics that promised empowerment to all members of socio-economically backward and socio-culturally oppressed identity-groups but has, in the reality of its identitarianised operation, inevitably left significant number of them in the lurch.

It is this renewed dialectic of reinforcement of modern-liberal Indianness and the socio-economic/socio-cultural polarisation against it that has, in all probability, electorally crystallised into a decisive pro-Modi vote. That has, for sure, been the case, at least, in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. For, the more this modern liberal identity of Indiannness is reinforced, the more class division is deepened and accelerated, leading to enhanced social polarisation that threatens and challenges the configuration of social power constitutive of such reinforcement. Something that would, therefore, inevitably lead the social configuration yielded by the reinforcement of the identity of liberal modern Indianness, to engage in a political manoeuvre to fob off that challenge in order to preserve and reinforce its power. It is such a move that has possibly contributed significantly to the ascendancy of Modi as a figure of politically institutionalised neoliberalism.

It must be understood here that the political offensive of this growing demographic of the modern national identity is constitutive of the reproduction of its social being that continues to be shaped and determined by the material and ideological-cultural demands unleashed by the process of economic liberalisation. Predictably, such offensive has been constant policy-bound, legal and illegal assaults on modes of social being that are ‘outside’ the demographic of the reconfigured modern national identity, precisely in order to subsume them. Such modes of social being, by virtue of their situation and position, are a barrier to the continuous reproduction of the mode of social being of the modern-liberal identity.

There is, however, an important detail about the outcome of the sixteenth Lok Sabha elections that must be taken into account here. The BJP voteshare is reportedly a little above 31 per cent. This is important not because one can then comfortably day-dream, in the manner of some deluded left-liberals, that had India followed the electoral system of proportional representation, the BJP, given its voteshare, would have been way below the half-way mark in Parliament.

Even if that were so, the intensified social differentiation wrought by a combination of identity-based social justice politics and economic liberalisation, ever since the 1990s, would have meant the continuance of unstable coalition politics. Now the problem with such politics, which would have continued to mirror the competitive anarchy characteristic of the neoliberal social formation, is not that it is unstable. The problem with it is that it is not unstable enough.

It is precisely the intensification of instability, which capital generates to then harness it before such intensification can push itself to its capital-unravelling limit, which is the source of all-round increase in precarity of social labour. It is this that makes such anarchy barbaric. The only way out of such ever-increasing precarity is not reversion to a previous less precarious mode of social being – something that is not only impossible but is fantastic nostalgia that fans the flames of precisely the kind of reactionary politics we are currently confronted with. The way out of such precarity lies, instead, in accentuating social divisions to an extent that they refuse to settle down to be harnessed, articulated and commanded by capital, leading to its collapse and overcoming.

In that context, it must be said that the kind of social instability that such coalition politics has hitherto mirrored is a kind of structured instability. It is instability at the phenomenal level through which capital as a structure of social power has continued to concentrate itself. And its continuance would have only meant the perpetuation of controlled anarchy that is decadent late capitalism as barbarism. But it is precisely such continuance that those deluded left-liberals suggest when they publicly exhibit their ridiculous dream of how the electoral system of proportional representation could have blocked Modi’s ascent this time around.

Given that almost all the opponents of rightwing politics of the sangh parivar have proved incapable, so far, of envisaging resistance in strategic terms that are beyond the coordinates of an electorally overdetermined socio-political system, it is very unlikely that they would have seized the capital-unravelling opportunity provided by such intensified, though controlled, social division, to push such division to its limit while simultaneously suppressing its structural articulation. In such a situation, the continuance of unstable coalition governments, which would have both reflected and reinforced the intensified generalisation of such structured anarchy would ultimately and inevitably have culminated in institutionalising such barbaric late capitalist decadence into a consensually acceptable and settled juridical-legal regime. Precisely the thing that stares us in the face now. Clearly, the dream of the deluded left-liberals, had it come true, would have brought us to where we currently stand through a detour that would not have, in any way, mitigated the pain of arriving at and living in the abode of neoliberal dictatorship.

The suffering inflicted by the barbarism of neoliberal capital, which its political dictatorship accentuates only by institutionalising it, would be no less now than if we came to it through the route dreamt of by those left-liberals. So, one is hard put to understand how such dreams and fantasies can be ingredients of an effective strategy to overcome neoliberalism and its politically institutionalised dictatorship.

In fact, it is precisely such misplaced dreams that have repeatedly facilitated, if not directly fuelled, passive revolutions ceaselessly accomplishing themselves in the garb of defending society against the politics of social domination. In other words, such dreams have enabled capital to keep expanding its remit as a dynamic of differential inclusion – or combined and uneven development – by breaking down existing forms of social cohesion to re-regiment society through the differentiation that such breakdowns inevitably yield.

In such circumstances, one can ill-afford to emphasise the importance of this detail by insisting, in a self-deluded, passive manner full of empty optimism, that it demonstrates that almost 70 per cent of the country’s electorate did not vote for the BJP. The point is that does not really matter. And this is not merely because India follows first-past-the-post electoral system.

Yet, this detail does posit hope. But its realisation lies beyond the remit of the system and its politics of electoral representation. In fact, one can begin to realise such hope precisely by destroying the system and its politics of electoral representation in the process of subtracting from it. For, as long as this system and its underlying structure is intact, they will always distort the facts in which such hopes reside by articulating and mobilising them into a continuous process of passive revolutionary regimentation. Something that has driven capital to this late decadent moment of historical development where the ceaselessness of such passive revolutionary regimentation has qualitatively transformed itself into neoliberalism that is a conjuncture characterised by the barbaric acceleration of extended reproduction of capital.

It is, therefore, not surprising at all that identitarianised social justice politics, as a paradigm and discourse of radical democratisation, has been steadily running into its limit. In the context of post-liberalisation India, all it has done for a while now is accelerate the extended reproduction of neoliberal capital by quickening its dynamic of actual subsumption. And that, as we have seen earlier, is exactly what has happened. The scale of Modi’s electoral victory is perhaps no more than a symptomatic expression and reinforcement of the rapidly growing redundancy of such politics as a paradigm of radical democratisation.

Unfortunately, that is lost as much on the electorally invested social democratic leftists and left-liberals as various non-electoral leftists, who claim to uphold authentic revolutionary working-class politics. Their near passive and complacent reliance — programmatically stated or otherwise — on the configuration of socio-economic and socio-cultural groups, generated by the discourse of social justice politics, as a bulwark against the rise of the Modi-led BJP demonstrates that. They have so far imagined that the fragmentation of a homogeneous national identity wrought by the politics of social justice would continue to effectively block the ascent of the sangh parivar’s rightwing politics of socio-cultural homogenisation and socio-economic regimentation. But it is time they accepted what they have failed to recognise so far.

The paradigm and discourse of social justice politics presented a radical possibility only because its operation effected class polarisations within backward and subordinate identities that had, till the advent of such politics, been relatively more cohesive. This possibility could, however, have come into its actualised own only if the class polarisations and the attendant fragmentation of the identities were leveraged by way of a radical-proletarian subjective intervention. It is precisely the failure of all varieties of the Indian Left on that score that has turned social justice politics, which was to begin with a great paradigm of radical democratisation, in a restorative and reactionary direction. The missed opportunity of further radicalising that paradigm by transforming it into a concretely articulated political discourse of open class anatagonism can, however, still be reclaimed, albeit under the condition of its growing irrelevance. In fact, it is precisely on account of such irrelevance that the faultlines opened up in society by the discourse of identity-based social justice politics need to be leveraged in overtly class-antagonistic terms.

III

The left and the left-liberal responses to the advance of rightwing politics have, so far, been the affirmation and defence of socio-cultural diversity without any understanding of how such diversity is orientated in its articulation. Thus the structural iron-cage within which such diversity is inscribed, and of which each of its constituent moments is an instantiation in cell-form, has largely been missed by the proponents and protagonists of such politics against rightwing homogenisation.

In such circumstances, if that structural iron-cage, thanks to its instantiation by every difference that is asserted, is today sufficiently reinforced to generate a consensus for it to be an institutionalised regime that maintains difference and diversity in an excessively regimented form, there should be no cause for surprise. The real question is whether difference is differential segmentation, which is exactly what the so-called radical politics of difference and diversity has so far unwittingly strengthened. Or, whether assertion of difference is an affirmation of the mutual partaking of such difference as singularities that is constitutive of the process of unraveling of the segmental structuring of difference? This is what revolutionary working-class politics is. Contrary to many of its proponents and all its difference-thinking leftist detractors, it is not a politics in which the proletariat, or the working class, functions as a sociologically closed category of a struggling subject-object that seeks to subsume all other struggles against different forms of social domination/oppression.

Difference-thinking, it must be admitted here, seeks to counter the tendency of closure that identity-thinking, which is also at the root of sociologised working-class politics, tends towards. Yet, difference-thinking, in failing to envisage the complete suppression and destruction of the tendency of valorisation and its horizon of identity-thinking, ends up buttressing the barbaric anarchy of neoliberal diversity. That is the horizon of value and identity as its own crisis-ridden accelerated reproduction that eventually culminates in its institutionalisation as a juridical-legal regime.

Capital is essentially socio-culturally-indexed differences as a mutual articulation of structured differentiality. The point is to work towards not merely defending those differences against homogenisation. Rather, the point is how those differences can come to coordinate with one another in their difference to emerge as a concrete social subject that is an affirmation and actualisation of the truth of non-differential, non-segmental operation of difference. That would be social reality as the real movement. But unless the former is acknowledged and rigorously worked through to be grasped in its socio-historical concreteness (Marx’s “real abstraction”), the latter will remain only an abstract ethicality (Marx’s “thought-concrete”) that awaits its transformation into politics by way of its concrete realisation (Alhtusser’s “real concrete”).

When Antonio Negri stresses on the utmost importance of figuring out the concrete dialectic of the technical and political compositions of the working class through determinate class analysis he is pointing exactly in that direction. In that context, the Popular Front model of cross-class alliance against fascism — which under various guises and labels is still the dominant model of left and left-liberal response to the advance of rightwing politics in this part of the world – is irrelevant.

IV

Anti-fascist Popular Front politics can now no longer be on the agenda of any desirable or even feasible project of radical social transformation. And that is regardless of whether it is articulated in the new-fangled, non-communist idiom of intersectionality and multiculturalist aggregation, or in the traditional communist idiom of alliance of historical blocs against big capital. Given the neoliberal conjunctural character of capital in its current historical moment, such politics is, as we have seen, ineffective. What we are, however, yet to recognise is that such politics is also outright counter-productive. It serves now to only reinforce and reproduce this late capitalist conjuncture and its concomitant political project of neoliberalism. Such politics is, therefore, a contradiction in terms. It seeks to counter Modi’s politics even as the modality of such struggle, which is integral to the reproduction of capital, now more than ever, consolidates precisely the neoliberal political project. Modi is merely its monstrous embodiment, and logical culmination. Such ‘anti-fascist’ politics of social cohesion, one can assert with hardly any risk of overstatement, has made its so-called progressive practitioners and purveyors complicit in the emergence of the dictatorship of neoliberal capital with a figure like Modi at its helm.

The Popular Front model is a politics of forging an aggregative coalition of socio-cultural difference or diversity in order to defend and champion such difference against the homogenising onslaught of a dominant social group. It is, therefore, a modality of politics that seeks to preserve difference without, at once, challenging the structure of differential inclusion and segmentation that difference in being difference instantiates, and which thus once again amounts to the reproduction of relationship of dominance and subordination as the condition of possibility for the regimented reinforcement of the structural principle that underlies such relationship.

Those committed to the project of radical social transformation in general, and working-class politics in particular, must, without further ado, come to terms with the irrelevance of the model of anti-fascist politics of Popular Front that tradition has bequeathed them. The Popular Front model, which had once proved to be an effective weapon against fascism, has now become like a gun that backfires on the one who wields it. And that is because now no struggle against a specific instantiation of capital (capital as the Hegelian concrete-universal) has any chance of success as long as it is not simultaneously also a prefigurative struggle for destruction of capital as the generalising mode of production and/or social organisation. If anything, struggles envisaged merely against specific forms of social domination in their immediacy — even as one defers the struggle against capital as a generalising mode of production/socialisation that such forms actualise through their specifying mediations – render the phenomenon of social oppression more unrelenting and widespread than ever. This is the neoliberal conjunctural salience of late capitalism as “totally administered society” (Adorno).

In other words, the Popular Front model of cross-class alliance against the bourgeoisie as a defined and dominant social group can now no longer be either an adequate or an effective moment of radical politics that finally seeks to destroy the law of value (or capital) by subtracting from it. For, it is this law of value – or identitarianisation as the structuring principle — that is the condition of possibility of social oppression. That has always been so since the beginning of the history of capital. What is different now is that unless the destruction of the law of value is envisaged simultaneously with the immediate struggles against various forms of social oppression that this law makes possible as its specific phenomenal instantiations, the latter will fail to get rid of the respective forms of oppression they are ranged against. Worse, they will only serve to further proliferate and intensify social oppression as ever-new phenomena.

V

To figure why that is so, we need to recognise the current level of historical development of capital, particularly with regard to its Indian (and south Asian) specificity, in terms of the structuring principle of its general dynamic.

The dialectic between primitive accumulation, which is often what is articulated by various orders of fascist and/or authoritarian regimes, and economic accumulation apparently based on free competition, a functional civil society and a democratic polity has run into a crisis. This crisis is about the dialectic becoming, in a tendential sense, less and less dialectical and more and more tautological (Negri). What this means is that the fascistic substance is constitutive of the liberal-democratic politico-ideological form less and less in a mediated, spatio-temporally displaced and/or cyclical kind of way, as was the case in the early capitalist conjuncture of embedded liberalism. Instead, this mutual constitutivity now occurs, more and more, in an immediate and spatio-temporally collapsed kind of way. As a result, the liberal-democratic form, as has been observed even earlier, is substantively illiberal and even fascistic in the immediacy of its operation. This is neoliberalism, which is neither fascism nor liberal-democracy, but a uniquely new socio-political reality.

That the post-Ram Mandir sangh parivar, for instance, slowly but steadily began shifting the terms of its majoritarian friend-enemy discourse from Muslims as enemies of Hindus, to ‘Islamic terrorism’ as the enemy of the secular Indian nation is arguably a crucial symptomatic elucidation of that. Tie it up with the new pattern of majoritarian pogroms that was inaugurated by the anti-Sikh carnage of 1984, and which found its ultimate expression in the Gujarat massacre of 2002, and it will become even clearer. For, what we see in those massacres is class struggle as class oppression becoming more and more openly socio-economic than earlier when it was virtually exhausted by its ideological-cultural mediations. For, what we had in those massacres, which was qualitatively different from what characterised earlier incidents and instances of majoritarian violence against religious minorities, was ethnic/communal cleansing expressing its capitalist materiality far more openly by being utterly unconcealed as economic cleansing.

That said, it must be added that capital as a system of social power constitutive of uneven development or differential inclusion cannot afford to cease being the dialectic it structurally is. As a result, the differentiated or segmented zones of formal subsumption and actual subsumption are maintained in their formal hierarchy even as this distinction is substantively collapsed precisely through the reinforcement and maintenance of that formal hierarchy. This is precisely capital (or the structural dialectic it is) as its own terminal crisis. A crisis that has rendered it an openly irrational force, or command, which maintains and reproduces the economic/extra-economic duality more as a tautology than a dialectic now.

The neoliberal reality (or project) is, therefore, much more than the phenomenal manifestation (Modi) it has currently congealed into. It cuts across the entire political landscape as a continuum of social corporatist, ‘strong messianic’ politics: it extends from the BJP’s majoritarian-nationalist developmentalism and the anti-corruption formations, including the AAP, to Modi’s holier-than-thou left-liberal adversaries and radical politics in all its shades of economism, militant reformism and politicism. The fight against neoliberalism — which must now, without doubt, focus its attack on the Modi regime as the principal institutional embodiment of such politics — will be truly effective only if it recognises, first of all, that in Modi it is targeting neoliberalism, not fascism. And, second, it concomitantly bases its strategy on rigorously and dispassionately working through the institutionalised emergence of this neoliberal project as the outcome of capital tending to completely realise itself as the dynamic of actual subsumption of living labour by dead labour.

Now, primitive accumulation was no less in the period between 1950 and 1990 on the Indian subcontinent. It was at work, quite ruthlessly and unsparingly, in the spatio-temporal zones (of formal subsumption) that were shaped, characterised and geographically demarcated as peripheries by it. Why, even those geographically delineated peripheral zones of ruthless primitive accumulation would also keep changing and expanding. But what remained unchanged at the qualitative level, in spite of such quantitative changes, is that the spatio-temporal zones of primitive accumulation and economic accumulation remained, more or less, both discursively and logically distinguishable. However, the qualitative change between then and now is that the zones of (extra-economic) primitive accumulation and economic accumulation are, tendentially speaking, less and less spatio-temporally displaced and separated from one another, and are becoming more and more (substantively) indistinguishable even as their hierarchised distinction is maintained and reinforced at the formal level precisely to enable this growing indistinction at the substantive level. Hence, the earlier insistence, pace Negri, on tautology: the dialectic as its own evident crisis.

This is clearly the reason why the world – the capitalist world-system to be precise – has as a whole moved, of course in a tendential sense, from the era of ‘localised’ states of exception (fascism, colonialism, totalitarianism and various other forms of authoritarian political regimes) then to what Giorgio Agamben calls “the generalised state of exception” (neoliberalism) now. One could even say that it is precisely the movement away from the earlier ‘localised’ states of exception that has yielded the current generalised state of exception, insofar as the successful movement away from the former failed to be constitutive of the overcoming of capital as their condition of possibility.

That the zones of primitive accumulation and economic accumulation are becoming more and more logically indistinguishable from one another, not despite but precisely because of their distinction at the level of discursive appearances, is borne out by the fact that the rate at which the organic composition of capital (c/v) – and/or regimes of accumulation – change now has become far more rapid than ever. Not just that, this rapid rate of change continues to accelerate ever more, and exponentially. In other words, the conjuncture now is distinguishable from the conjuncture then by the fact of economic cycles – the interregnum between one form of organic composition of capital and another – becoming progressively shorter, and the concomitant regimes of accumulation becoming less and less stable. This increasing rapidity of change in the organic composition of capital, which can also be described in terms of the ever-shortening duration of economic cycles, means that primitive accumulation and economic accumulation are virtually co-incident. So much so that the extra-economic operation of capital as sheer force has become almost permanent in all its discursively distinguishable moments.

The qualitative change in technology regimes — signalled by the entry and rapid generalisation of electronics, microelectronics, robotics and informatics — has led not only to an unimaginable increase in the rate of relative surplus-value extraction but also to a situation, wherein relative surplus-value extraction amounts, almost at once, to an enhanced rate of absolute surplus-value extraction as well. If we look at the changes in the labour process in terms of the “technical composition” of the working class (social labour) across various constituent sectors of our entire social-industrial life, we will see that even where there has been no lengthening of the average workday, albeit such instances are rare, the new qualitative changes in technologisation have wrought productivity increase through incredible levels of intensification of work and drudge than earlier for the same duration of the average workday. So much so that one’s entire cognitive life and significant parts of one’s affective life have got fully integrated into the production process. In fact, in some traditional sectors of immaterial or intellectual production, the length of the average workday might even have declined a little compared to earlier but that has been much more than neutralised by the increased intensity of work that wage-labourers in those sectors have to contend with now.

And how else is this increased and increasing intensification of work enforced, than through a more intensive disciplinary operationalisation of the everyday work-ethic? That includes both traditional forms of ideologico-repressive mechanisms of peer pressure and mutual surveillance, and new forms of intrusive surveillance to measure output and watch out on everyday subversion through devices fixed to workstations and so on. What else would this be other than the increasing pervasiveness, through intensification, of extra-economic disciplining and its near permanence in almost every moment of lived time rendering virtually all of social life both productive and coercive at the same time?

What must also be mentioned here is that this qualitative shift in technology regime is a dialectical feedback loop of both cause and consequence with regard to the current conjunctural salience of neoliberalism. This shift has been on account of the gradual accumulation of quantitative changes in the organic composition of capital through the past several centuries due to the conflict between living labour and dead labour. Something that is registered and recognised as competition within the politico-economic horizon of capital. That is precisely the reason why we ought to describe both quantitative and qualitative changes in the organic composition of capital also as quantitative and qualitative shifts in productive forces. Such continual quantitative changes in the organic composition of capital have progressively accentuated the conflict between living labour and dead labour. This, in turn, has necessitated more quantitative changes in the productive forces that have finally yielded a qualitative leap in productive forces, and a concomitant qualitative shift in the regime of accumulation. What this qualitative shift in the twinned regimes of technology and accumulation has yielded (and continues to yield with ever-increasing ferocity) in various sectors of the economy is a crisis that is about the declining capacity of capital as a social relation of production to further diminish socially necessary labour time and extract more surplus labour time.

Capital now seeks to resolve this crisis by tending more and more towards rendering the spatio-temporal zones constitutive of realisation of value – circulation, consumption and social reproduction — into zones of value-creation and surplus value-extraction in their own right. This has meant the substantive transformation of non-work socialisation and life — precisely by maintaining and reinforcing such non-work socialisation and life as the forms they have traditionally been – into productive work. This has led to the emergence of biocapitalism, wherein life itself is production and production life.

In such circumstances, when the entire social formation, and life itself, has been transformed into an industrial complex (social factory) — a process that continues to intensify and accelerate — society cannot be defended by merely fighting against the dominant and elite social groups, and the oppression they threaten society with. Of course, such struggles against corporate-capitalist marauding and/or the oppression wrought by dominant and elite social groups will probably still continue to constitute many of the tactical moments of the larger battle against capitalism. But what those struggles must absolutely ensure if they are to fulfil their destiny as tactical moments of the larger battle to unravel and overcome capital is that they in their various specificities are immediately co-terminus with the actuality of the larger battle. Such a situation will emerge when struggles against various forms of social oppression and domination envisage themselves, and their mutual coordination, in terms of working-class solidarity. This is not merely a matter of semantics, though. The modality of working-class solidarity is the continuously uninterrupted process of “struggle in unity, unity in struggle” (Mao Zedong). A process that is constitutive of labour in self-abolition through subtraction from capital as the mode that structures the entire social formation as a system of differential inclusion.

Clearly, an aggregative alliance of oppressed social groups against the institutionalised embodiment of that mode of social organisation is by no means an insurrectionary configuration of working-class solidarity. Such a configuration, in being the continuously uninterrupted process of struggle in unity, unity in struggle, will be constellational.

So, let us join our voices to the poet’s and say, “there are no barbarians any longer”. That is not because we have vanquished barbarism, but precisely because we all have, in fighting the barbarians, become barbaric. That is something we must recognise and acknowledge if we are to behead the monster — which has risen over our heads as a concentration of our very own barbaric energy. And find redemption.

-

Milwaukee vigil remembers Al Nakba, calls for solidarity with Rasmea Odeh

Milwaukee, WI – Dozens of Palestine solidarity activists gathered on the lakefront here, May 15, during rush hour to commemorate Nakba Day.

Al-Nakba or “The Catastrophe” refers to May 15, 1948, the day after Israeli “Independence Day.” In 1948, 700,000 Palestinians were expelled by Zionist troops under the pretext of establishing a Jewish state of Israel on Palestinian land. 400 Palestinian villages were depopulated and taken over or destroyed by the Israelis, laying the foundation for the continuing occupation of Palestine.

In response to continuing occupation and oppression of Palestinian people by the U.S. and Israel, activists held signs demanding “End U.S. aid to Israel,” and “Drop the charges against Rasmea Odeh!”

Members of the Milwaukee Palestine Solidarity Coalition responded to the national call to action to support Rasmea Odeh, a veteran Palestinian activist. Odeh is a 66-year-old community organizer who has dedicated her life to the empowerment of Palestinians, especially Palestinian women. She is the victim of a U.S. government attack which is intended to jail or deport her for allegedly lying on a 20-year old immigration form. Her trial is set to begin on June 10 in Detroit.

As the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel grows more successful by the day, activists are facing repression from the U.S. government. Activists in Milwaukee say they will continue to win victories for the BDS movement while defending Palestinian community leaders like Rasmea Odeh from political attacks.